I spoke to Jia on her recent trip to London, in the midst of a whirlwind press blitz.ĪK: So, you’re doing a lot of interviews at the moment. In a time of deafening noise and chaos, she can single out some clear note of lucidity and reveal to us the value, if any, in listening through the din in the first place. Instead of viewing her as someone who speaks for us, it’s better to view Tolentino as a kind of interpreter. Tolentino’s writing has garnered praise and accolades not because of its zeitgeistiness, but because of its clarity, offering no lessons or easy takeaways. It’s for this reason that she is often referred to as the voice of her generation, or as the Susan Sontag of our times.īut maybe that’s reductive.

She provides no solutions to the problems she identifies, instead simply cutting through the rotten parts of our culture with precision, doing so by taking a long, hard look at the culture around her and her role in it. In each one Tolentino identifies some source of corrosion or uncertainty unique to late capitalism. The essays in Trick Mirror move through ecstasy and loss of faith to barre classes as a means of self-optimisation and the prevalence of scams in millennial culture.

Tolentino, who is 30, is fully aware of how much of her life she has spent broadcasting herself. Now here we are in the future, and whether it’s a spot on a reality TV show or just a viral tweet, all of us are conscious of the ways we present ourselves, and what happens when they get projected far beyond us. In 1966, Andy Warhol said that in the future, everyone would be famous for 15 minutes and the potent confluence of social media and self-broadcasting seems to represent the apex of that maxim.

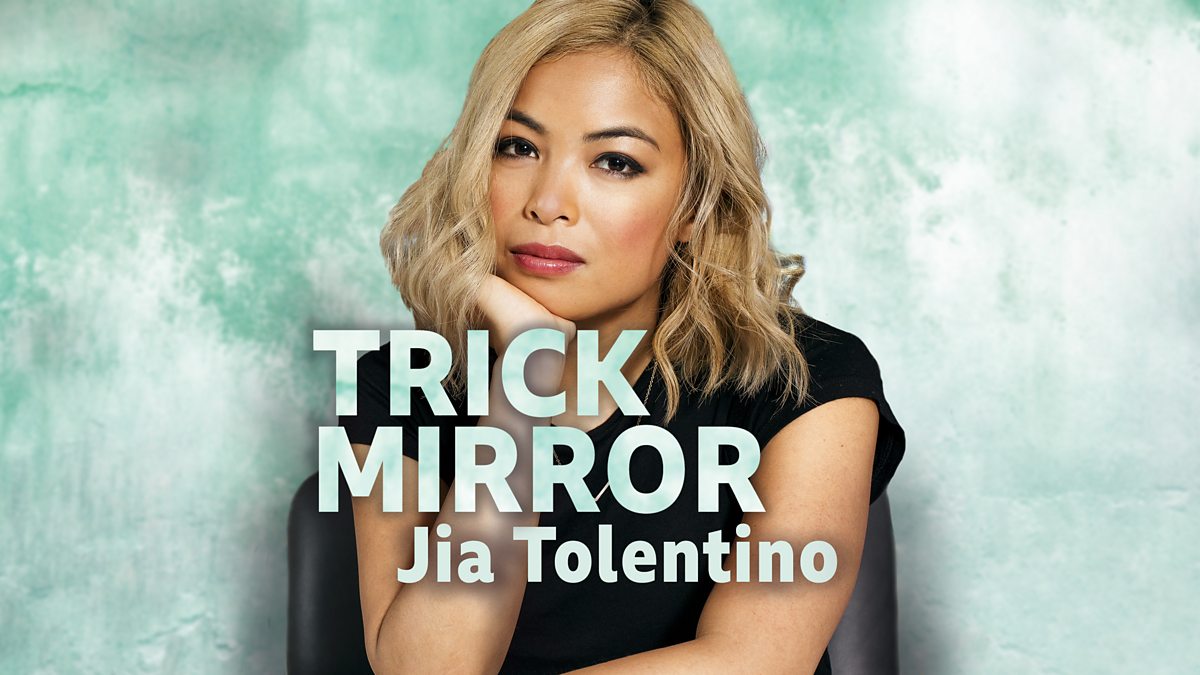

Except that it’s not exactly a bombshell. In the second essay of Trick Mirror, Jia Tolentino, the author and New Yorker staff writer, drops something of a bombshell: at 16 she appeared on Girls vs Boys, an early example of the reality TV genre that has come to dominate contemporary pop culture.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)